Automation and Skill Retention

Thursday, February 5, 2026

Anthropic recently published research examining how AI use impacts skill development and efficiency:

In a randomized controlled trial, we examined 1) how quickly software developers picked up a new skill (in this case, a Python library) with and without AI assistance; and 2) whether using AI made them less likely to understand the code they’d just written.

And the findings:

We found that using AI assistance led to a statistically significant decrease in mastery. On a quiz that covered concepts they’d used just a few minutes before, participants in the AI group scored 17% lower than those who coded by hand, or the equivalent of nearly two letter grades. Using AI sped up the task slightly, but this didn’t reach the threshold of statistical significance.1

They conclude that “Given time constraints and organizational pressures, junior developers or other professionals may rely on AI to complete tasks as fast as possible at the cost of skill development—and notably the ability to debug issues when something goes wrong.”

Their findings echo Lisanne Bainbridge’s “Ironies of Automation,” examining the “ways in which automation of industrial processes may expand rather than eliminate problems with the human operator.”2

Bainbridge identifies a variety of ways in which cognitive and physical skills atrophy as more of a process is automated. The first two directly speak to the specific question examined by Anthropic, and the remaining speak to problems that seem likely:

- Control skills: “physical skills deteriorate when they are not used, particularly the refinements of gain and timing. This means that a formerly experienced operator who has been monitoring an automated process may now be an inexperienced one…When manual take-over is needed there is likely to be something wrong with the process, so that unusual actions will be needed to control it, and one can argue that the operator needs to be more rather than less skilled, and less rather than more loaded, than average.”

- Longterm knowledge: “efficient retrieval of knowledge from longterm memory depends on frequency of use (consider any subject which you passed an examination in at school and have not thought about since)…knowledge develops only through use and feedback about its effectiveness.”

- Monitoring: “it is impossible for even a highly motivated human being to maintain effective visual attention towards a source of information on which very little happens, for more than about half an hour. This means that it is humanly impossible to carry out the basic function of monitoring for unlikely abnormalities which therefore has to be done by an automatic alarm system connected to sound signals…A more serious irony is that the automatic control system has been put in because it can do the job better than the operator, but yet the operator is being asked to monitor that it is working effectively.”

- Operator attitudes: “One result of skill is that the operator knows he can take-over adequately if required. Otherwise the job is one of the worst types, it is very boring but very responsible, yet there is no opportunity to acquire or maintain the qualities required to handle the responsibility. The level of skill that a worker has is also a major aspect of his status, both within and outside the working community. If the job is ‘deskilled’ by being reduced to monitoring, this is difficult for the individuals involved to come to terms with. It also leads to the ironies of incongruous pay differentials, when the deskilled workers insist on a high pay level as the remaining symbol of a status which is no longer justified by the job content.”

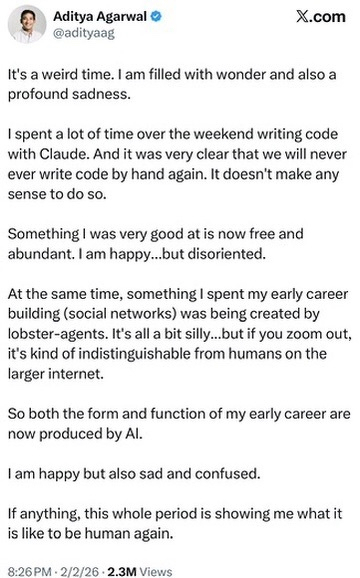

I believe we should expect all of the above to apply just as much to cognitive automation. The Anthropic finding is one bullet point, and it does not take much looking to find concerns about, e.g., loss of status:

As cognitive work becomes more automated, we should expect the above to become more pronounced.

It also raises serious questions concerning monitoring and oversight. As more and more cognitive labor is automated, how can breakdowns in processes be identified and rectified? From the outside, it does not appear that there are good answers to these questions, although they are doubtless in part the focus of alignment research.

Ultimately, there is no escaping the burden of judgment. The more a process or system is automated, the more responsibility is concentrated on singular moments of judgement in moments of acute uncertainty.